The Remarkable Story of a Howell Torpedo

In 2013, Navy dolphins unearthed one of the world’s rarest weapons: a 19th-century Howell torpedo lost off San Diego in 1899. Only five Howell torpedoes still exist today (two of which are currently on display at the U.S. Naval Undersea Museum).

You can see the Howell torpedo discovered by Navy dolphins in our temporary exhibit, Marine Mammals: The Navy’s Super Searchers,* and explore the torpedo’s full story in this online exhibit!

Use the tabs below to discover how Howell torpedoes work, the history of their invention and use, the story of how Navy dolphins discovered one, and how conservators saved the torpedo after it spent 112 years underwater.

* The Howell torpedo is generously on loan for the exhibit from the Naval History and Heritage Command Underwater Archaeology Branch.

The Invention and History of the Howell Torpedo

The Howell torpedo was the first self-propelled torpedo developed by the United States and used in service in the U.S. Navy. It was invented by Lt. Cmdr. John Howell in the 1870s and 1880s, after English engineer Robert Whitehead debuted the world’s first successful torpedo in 1866.

The Howell torpedo was the first self-propelled torpedo developed by the United States and used in service in the U.S. Navy. It was invented by Lt. Cmdr. John Howell in the 1870s and 1880s, after English engineer Robert Whitehead debuted the world’s first successful torpedo in 1866.

Click any image to view at a larger size.

The Whitehead Torpedo

The Whitehead Torpedo

Robert Whitehead developed the first experimental model of an automobile torpedo in 1866. Propelled by a two-cylinder, compressed-air engine, this early version could travel 200 yards at a speed of 6.5 knots. By 1868, Whitehead had refined his design and began selling two sizes of his MK 1 torpedo to navies around the world: an 11-foot, 8-inch model with a 40-pound guncotton explosive and a larger, 14-foot model with a 60-pound guncotton explosive. Both performed similarly, running at 8–10 knots with a range of 200 yards.

Towards An American Torpedo

Towards An American Torpedo

Whitehead’s torpedo caught the attention of Vice Adm. David Porter, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy. At Porter’s orders, the Bureau of Ordnance established a Torpedo Station at Newport, Rhode Island, in 1869 to develop an American torpedo. Between 1870 and 1880, Torpedo Station engineers and other American inventors produced designs for a handful of unsuccessful torpedoes such as the Torpedo Station’s “Fish” torpedo (left), the rocket-propelled Barber torpedo, the chemically-propelled Lay torpedo, and the compressed-air Ericsson torpedo.

John Howell

John Howell

In 1870, while heading the Department of Astronomy and Navigation at the U.S. Naval Academy, Lt. Cmdr. John Howell (left) began designing a torpedo in his spare time. The design of Howell’s torpedo centered on a flywheel inside the torpedo that provided propulsion while stabilizing the torpedo in the water, an idea he patented in 1871. Over the next ten years, John Howell refined and tested his torpedo until he achieved an improved working model in 1881.

A Torpedo Contest

A Torpedo Contest

In 1883, Congress appropriated $100,000 for the purchase and manufacture of torpedoes “after full investigation and test” before a “Torpedo Board” of naval officers. A letter issued by the Torpedo Board described the qualities desired in the winning torpedo, including “accuracy, range, velocity, certainty of handling, [and] destructiveness.”

John Howell presented his torpedo (left) before the Torpedo Board in December 1883, competing against two surface-running, rocket-propelled torpedoes put forward the American Torpedo Company and a private inventor, Asa Weeks. Howell’s torpedo was the only one chosen for further consideration.

Howell Torpedoes Join the Fleet

Howell Torpedoes Join the Fleet

Following additional testing over the next few years, the Navy established a test program for Howell torpedoes. By July 1886, the weapons were operating consistently and successfully during test runs. A member of the Bureau of Ordnance testified before the Senate Committee on Ordnance and Warships later that year, calling the Howell torpedo the “most valuable American [self-propelled] torpedo that has yet been invented for naval use.”

In 1888, John Howell sold his torpedo patent rights to the Hotchkiss Ordnance Company, based in Providence, Rhode Island. The Navy ordered the manufacture of 30 Howell torpedoes in January 1889, but it would be almost three years before Hotchkiss delivered the first ten Howell torpedoes. The Navy added an additional 20 torpedoes to the contract in 1894, for a total of 50 Howell torpedoes purchased.

The Decline of the Howell Torpedo

Howell torpedoes entered service in 1895. By 1898, thirty-five Navy torpedo boats had been commissioned to carry and fire self-propelled torpedoes, most of which were Howell torpedoes. Their service life was short-lived. The Navy had contracted for 100 Whitehead torpedoes in 1892, concerned they might fall behind the many foreign navies who had previously adopted the Whitehead. The same year Howell torpedoes joined the Fleet, Whitehead torpedoes did too. As ships’ torpedo tubes were relocated below the water, the launch of Howell torpedoes from steam turbine-powered torpedo tubes became prohibitive, and the Howell fell out of use by the late 1890s and early 1900s.

The Design of the Howell Torpedo

A Superior Design

Lt. Cmdr. John Howell’s design for his eponymous torpedo (below) was innovative and sophisticated, especially for a nineteenth-century torpedo. Most naval technology historians believe that the Howell torpedo was equal or superior to the Whitehead torpedo, despite the latter’s success. The Howell matched the Whitehead in speed and range, but was smaller, lighter, more accurate, carried more explosives, and cost half the cost to manufacture, operate, and maintain.

Click any image to view at a larger size.

Howell Torpedo Specifications

Length: 132 inches

Diameter: 14.2 inches

Weight: 580 pounds

Warhead: 100 pounds wet guncotton

Speed: 25 knots

Range: 400–800 yards

Innovative Propulsion

Innovative Propulsion

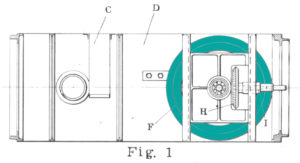

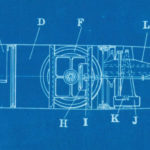

The most innovative aspect of the Howell torpedo was a 132-pound flywheel (highlighted at left) located in the weapon’s midsection. In a clever feat of engineering, the flywheel powered the torpedo and provided a gyroscopic stabilizing effect. When spun to its full speed of 10,000 revolutions per minute, the flywheel supplied enough stored energy to propel a Howell torpedo 400–800 yards through the water.

Two propeller shafts connected the flywheel to the torpedo’s propellers: two triple-bladed propellers which rotated in opposite directions. Because the torpedo slowed as the flywheel’s speed dissipated, Howell designed the propeller blades to increase pitch to maintain consistent speed.

Launching

Launching

Aboard a torpedo boat, a steam turbine attached to the starboard (right) side of the launching torpedo tube spun the Howell’s flywheel up to 10,000 RPM. Once at full speed, the torpedo could be launched by pulling on the tube’s firing lever. This released the tube’s hold on the torpedo and fired the propulsion charge of black powder.

As a Howell torpedo sped through the water, it was stabilized both by the gyroscopic effect of the flywheel, and by a pendulum in the afterbody that adjusted the torpedo’s rudders to keep it from rolling or changing course. Because it was powered by the flywheel, versus a compressed air flask like the Whitehead torpedo, the Howell left no telltale wake to identify its path.

The Discovery of Howell #24 by Navy Dolphins

Two trained Navy dolphins detected a rare Howell torpedo (serial number 24) in March 2013 as they trained off the coast of San Diego, where the Navy’s Marine Mammal Program is based. The animals used their echolocation ability to discern the torpedo’s presence under seafloor sediment.

Dolphins Trained to Detect Mines

Dolphins Trained to Detect Mines

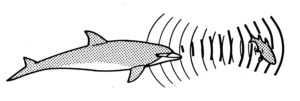

Since 1963, the U.S. Navy has trained dolphins and sea lions in the Navy Marine Mammal Program to detect objects underwater. Of the three types of missions the animals perform, the most difficult is detecting unexploded mines. Dolphins carry out this type of mission using their echolocation (biological sonar) to find mines tethered to the seafloor, resting on the bottom, or fully buried in sediment.

Detecting these mines, which can pose dangers to ships and bases, allows explosives experts to retrieve and disarm them before they can cause any harm. The mines are not dangerous for the dolphins that find them. Mines are designed to detonate by sensing the magnetic presence of ships (which dolphins do not possess) or through physical contact with ships that weigh many tons (which means a 400-pound dolphin cannot trigger them).

Dolphin Echolocation

Dolphin Echolocation

Dolphins use biological sonar called echolocation to “see” underwater. A dolphin echolocates by making clicking noises which send sound waves into the water. When the sound waves hit something, echoes bounce back to the dolphin. The returning echoes provide information about the object’s size, shape, distance, density, and speed. It is so precise that dolphins can distinguish between a kernel of corn and a ball bearing from 50 feet away, in less than a second. Echolocation can even penetrate through some substances, which is why dolphins can detect mines buried under the seafloor.

A Remarkable Discovery During Routine Training

A Remarkable Discovery During Routine Training

The Navy Marine Mammal Program is based in San Diego. Animal trainers regularly run practice drills in training areas off the San Diego coast. In early March 2013, a dolphin named Ten signaled a find during her daily training. Her trainers were surprised as they had not planted a practice target in that location. A week later, when another dolphin named Spetz reported an object in the same location, his trainers directed him to mark it for divers to investigate.

The divers were astounded to discover Ten and Spetz had found the tail section (bottom left) of a rare, nineteenth-century Howell torpedo. Recent storms had stirred up enough seafloor sediment that the dolphins’ echolocation could detect the Howell tail, which was more than 90 percent buried. At their trainers’ direction, the dolphins searched the training area for the other sections of the torpedo. The dolphins readily located torpedo’s midsection about ten feet from where the tail section was located. The torpedo’s exercise head was never found.

The History of Howell #24

The History of Howell #24

Using the torpedo’s serial number 24 (stamped on the tail section) and archival records, historians pieced together the weapon’s individual history. Because it was discovered in its exercise configuration, researchers hypothesized it might have been lost during a training exercise. They identified five ships that tested Howell torpedoes on the West Coast during the 1890s, and reviewed their ship’s logs.

The log of battleship USS Iowa (BB 4) revealed the details of Howell #24’s loss. The torpedo was lost by Iowa‘s crew in December 1899 during a series of torpedo practice exercises off the coast of San Diego. The battleship’s log definitively confirmed this history with an entry for December 20, 1899, that noted “…Target practice with torpedoes. Lost H. Mark I, No. 24 torpedo.”

Conserving Howell Torpedo #24

After spending more than 112 years in underwater, Howell torpedo #24 needed special short-term and long-term treatment to keep it from deteriorating.

After spending more than 112 years in underwater, Howell torpedo #24 needed special short-term and long-term treatment to keep it from deteriorating.

Immediate Care

Immediately following the torpedo’s discovery in March 2013, staff at the Marine Mammal Program (MMP) consulted with experts at the Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) Underwater Archaeology Branch for advice. At the conservators’ direction, MMP staff immersed the sections in large tubs of fresh water. The torpedo had absorbed salts from its years underwater which could form crystals and break apart should it be allowed to dry in air. Soaking it in fresh water prevented this deterioration until conservators could begin formal treatment.

Treatment Begins at NHHC’s Underwater Archaeology Branch

Treatment Begins at NHHC’s Underwater Archaeology Branch

In May 2013, after being certified inert by explosive ordnance disposal personnel, Howell torpedo #24 was flown across the country to the Naval History and Heritage Command’s headquarters in Washington, D.C. Conservators with the Underwater Archaeology Branch began the work of slowly extracting salt deposits from the torpedo in a process called desalination. They first placed the sections in water, followed by three months in specially-formulated chemical baths.

Developing a Long-Term Treatment Plan

Developing a Long-Term Treatment Plan

Conservation requires a great deal of knowledge of many subjects, including chemistry and the materials an object is made of. In the case of the Howell, conservators also had to understand its engineering as some components needed to be disassembled to perform the conservation work.

In January 2014, a team of conservators began the 18-month conservation effort to treat and stabilize the Howell torpedo sections. The conservators studied original documents describing the Howell, including an 1896 technical manual, to understand its inner components and to develop a detailed treatment plan.

18 Months of Meticulous Conservation

18 Months of Meticulous Conservation

Conservators painstakingly removed more than 220 pounds of concretions (mineral buildups) and sediment that was present on and within the torpedo sections. They performed this work using hand tools (some custom-made) and pneumatic chisels. Limited access inside the torpedo, as some components could not be disassembled safely, made the process slower and more difficult.

Both sections were chemically stabilized by placing them in chemical baths for 5–6 months, which slowly removed chloride that the metal had absorbed during its many years in salt water. The chloride was extracted through a combination of osmosis and electrolysis techniques. After the sections were deemed to be sufficiently stabilized, they were carefully cleaned and given a protective surface coating. The full conservation process was completed in July 2015, ensuring this rare artifact will be around for many more years to come.

Photo Gallery

Explore images of Howell torpedo #24, sketches and diagrams of Howell torpedoes, and photos of Navy marine mammals performing missions in this gallery.

Click on any image to view at a larger size.

Howell Torpedo #24

Howell Torpedo (General)

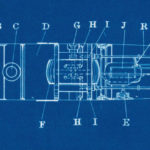

1896 Howell Torpedo Technical Manual (click to view or download) |

||

|

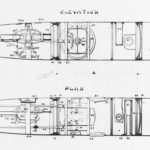

|

|

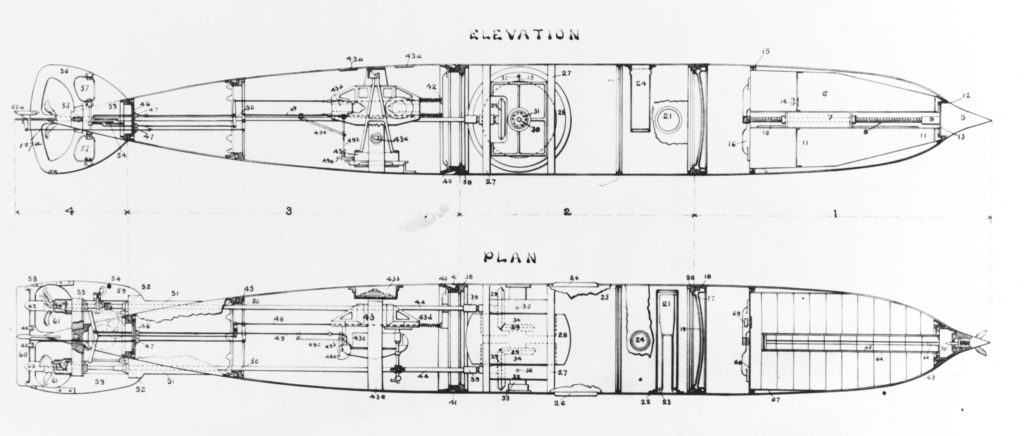

| Drawings showing a side view (upper image) and top view (lower image) of a Howell torpedo. | A side profile scaled drawing of a Howell torpedo, from the torpedo’s 1896 technical manual (see above link). | A top-view scaled drawing of a Howell torpedo, from the torpedo’s 1896 technical manual (see above link). |

|

|

|

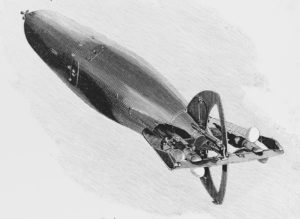

| A drawing from the Journal of Scientific American Coast Defense Supplement showing an aft (back) view of a Howell torpedo, 1898. | A Howell torpedo on the deck of torpedo boat USS Stiletto, 1896. | An undated photo of a Howell torpedo. |

|

|

|

| A drawing from the Journal of Scientific American Coast Defense Supplement showing the Howell torpedo’s flywheel and steering gear, 1898. | An early test firing of a Howell torpedo from torpedo boat USS Morris, circa 1894. | A Howell torpedo on permanent display at the U.S. Naval Undersea Museum, which is one of only five Howells still in existence. This Howell is serial number 35. |

Navy Marine Mammals